“I don’t drink. You know, the routine grind drives me to drink. Tragedy, I take straight.”

-Alex Cutter, Cutter’s Way (1981)

One of the things I love about movies is their ability to take me by surprise. I’m not talking about a wild twist ending, or some deus ex machina shit. I’m talking about the deep stuff, the stuff that engages and challenges my perception of the movie’s plot, subtext, and characters. Maybe it even influences how I look at things in my own life. It’s not often this happens, but when it does, it’s refreshing, exciting and inspiring. That’s what happened the night chose to watch the 1981 Ivan Passer film, Cutter’s Way.

Cutter’s Way follows the story of Richard Bone (Jeff Bridges) who, after his car breaks down in an alley one rainy night, witnesses a car slowly roll up, a mysterious man get out, dump something large into a trash can and then almost plows through Bone with his car as he makes a quick getaway from the scene. Bone doesn’t give it a second thought until the next day, when it’s revealed that a girl was viciously murdered and disposed of in that trash can the night before. Worse, Bone is the prime suspect. After being questioned and released by the police, Bone is at a parade with his friends, Vietnam veteran Alex Cutter and his wife Mo, and thinks he spots the man he saw the night before in the alley marching in the parade. It’s local business tycoon J. J Cord. This gains Cutter’s attention. In a few short moments Cutter begins to concoct an elaborate blackmail plot to oust Cord for the crime he thinks he’s committed. What follows is not your run of the mill conspiracy movie. Sure it’s got all the moments conspiracy movies have, but this movie is really about the lives of the people involved and the distractions they create for themselves to ignore the reality of their lives.

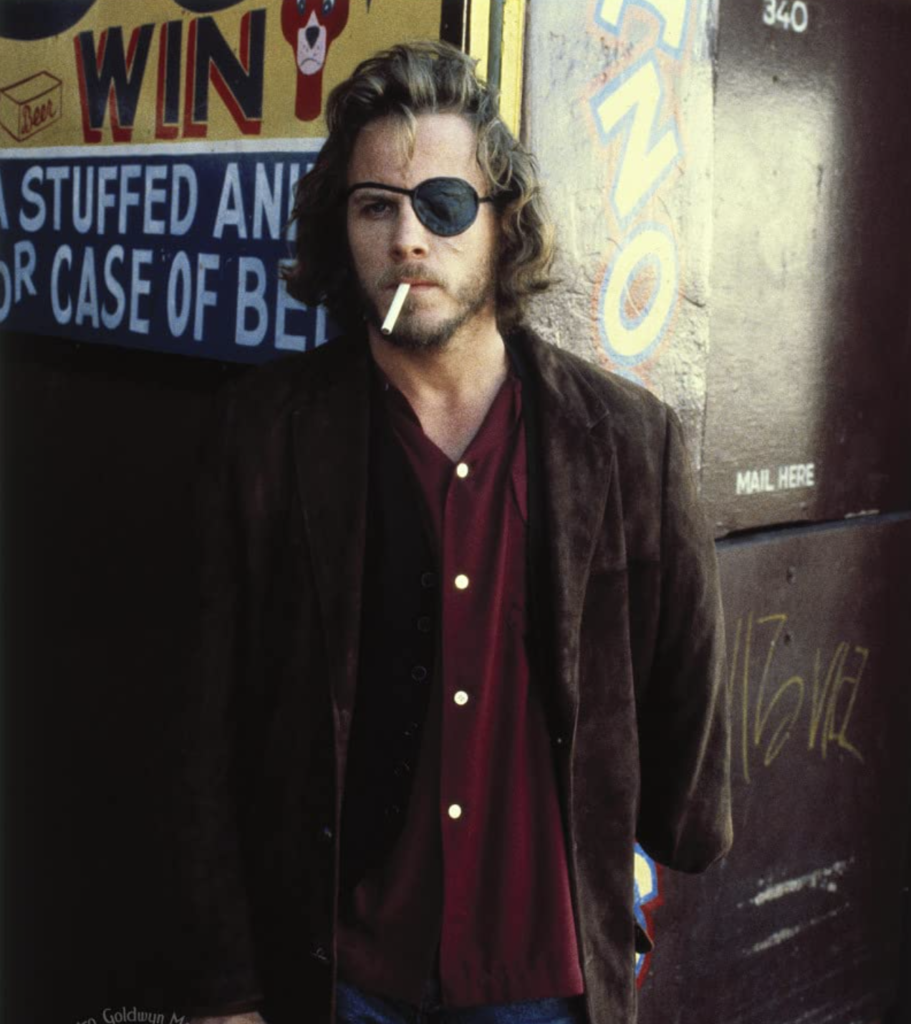

Half crippled, eye patch wearing, alcoholic Vietnam vet, Alex Cutter, played by John Heard, has been chewed up and spit out by American ideology. He’s a simmering pot of disenfranchisement, waiting to boil over onto everyone and anyone around him. He’s seen humanity at its worst and he’s not buying the facade that America is selling in a post Vietnam War America. He knows we’re not all in this together. Systemic racism, gender and financial inequality is alive and well in 1981 and Alex Cutter isn’t reluctant to point it out and in some ways embrace it in the name of truth, forcing you to see it and acknowledge it, much like his own existence. He knows cultures are still held down by rich powerful men, or those responsible, as he calls them in the film. Alex Cutter walks a fine line of truth and lies effortlessly and that is the brilliance of John Heard’s performance.

One of the exciting things, and also one of the disappointing things, that stood out to me about Cutter’s Way was that I clearly didn’t know shit about John Heard. Prior to this movie I knew Heard best for his role as the corporate jerk in Big and as the dad in Home Alone. Obviously I had seen him in other films, but he was always cast into one of those two roles. But Alex Cutter was something I’d never seen him do before and it was fantastic! Alex Cutter, is full of intensity, aggressiveness and sadness. Heard crafts a performance that left me wondering, How was he not one of the most famous character actors in history!? His performance goes from raw and chaotic to calculated and manipulative in the time it takes him to take a pull from his Jim Beam bottle. He revels in drunken arrogance when doubling down on the blackmail plot and can quickly change gears to be a sheepishly, somber, wounded Vietnam vet to con a police officer from giving him a ticket for drunk driving. Heard never lets the audience or the other characters forget that he is in control of the situation, no matter how out of control the circumstances become. But when the real tragedy strikes, he’s a whole different animal. Heard really excels as Alex Cutter in the quiet moments – the moments where Alex can’t manipulate the situation or brazenly steamroll an argument by yelling over someone about the falsehoods of the American Dream. All he can do in situations like this is sit quietly and try and cope with the realities of his life. This is the real stuff, the stuff he takes straight. The stuff i’m referring to is the truth.

Alex controls most of the situations around him to avoid dealing with reality of his own life. He would have much rather live the paranoid narrative he’s weaved out of the girls murder, then face his own demons and choices. No other moment in the film encapsulates this idea quite like how he mourns the death of his wife Mo. Alex knows he’s responsible for her death but is unwilling to admit it to himself. He knows if he takes responsibility for her death, it becomes real. His performance, for the first time in the movie, is sober, quiet and angry. In this moment he makes the choice to not accept any responsibility for her death. Instead, he recommits on the conspiracy he’s been weaving and concludes that J.J Cord killed the girl and Mo (It’s never confirmed Cord killed the girl or Mo but more on this later). Cutter submerges his responsibility and channels his feelings of loss into one last desperate attempt to take down Cord. It’s a suicide mission that Cutter is willing to take because he has nothing left to lose.

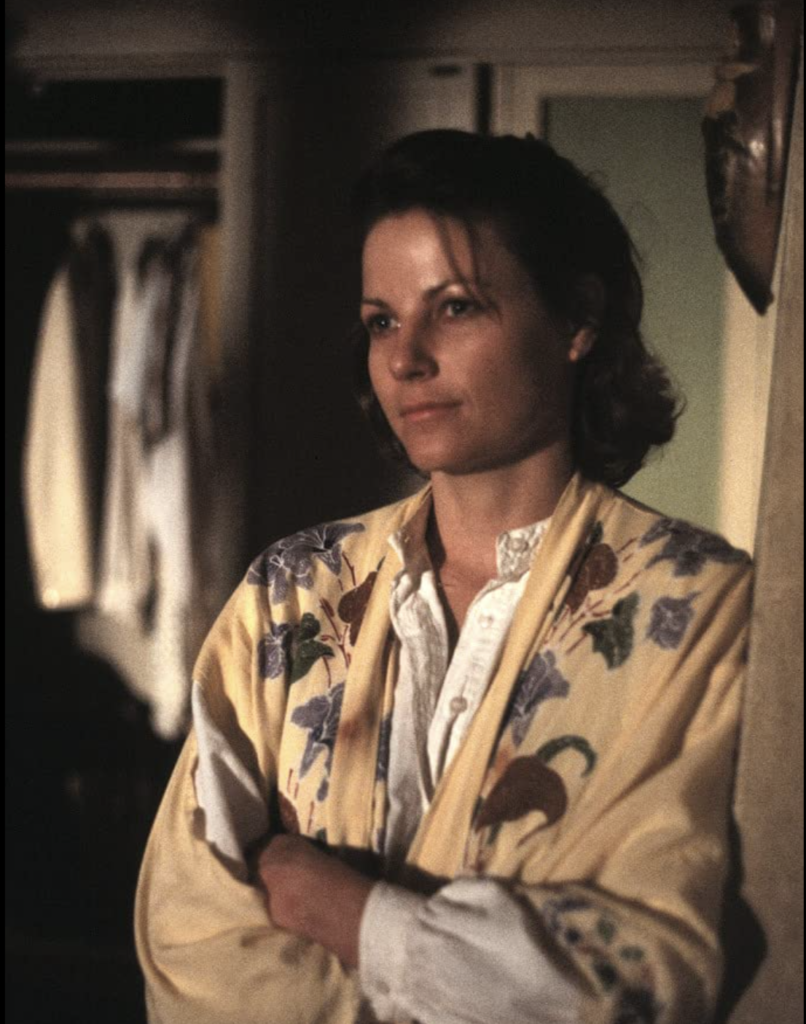

Credited only as Mo, you’d think Lisa Eichhorn’s role in Cutter’s Way would be another quiet role for a woman in 70s/80’s cinema. A damsel in distress, love interest or the voice of reason. Mo does act as the voice of reason throughout the film, but she is so much more than that. Eichhorn delivers a performance that broke my heart. Playing the wife to Alex Cutter, Mo shows just how far hope can take you and what happens when it takes you to the fringe.

Mo is a broken woman. Her marriage to Alex Cutter hasn’t been the same since he returned home from Vietnam. He’s half the man he was, both physically and metaphorically, but Mo refuses to give up hope that the man she once loved will return. She wakes up every day thinking today might be the day it goes back to how it was, but everyday it gets a little worse. She is sad, miserable and wallowing in all of it. She’s a woman who cries in the dark. In a lot of ways, her sadness is as crippling to her as Cutter’s injuries are to him. She feels invisible from the years of being stepped on by Alex’s drunken rants and raves. One of her most vulnerable moments is when she reveals to Bone that she has to look at herself in the mirror to see if she is still here. Eichhorn shows us that an invisible existence is worse than death itself.

Eichhorn’s ability to act on multiple levels using all the gifts she’s been given is a huge part of what makes her character work so well on screen. I know there are plenty of actors that act with their eyes or act with their body, but what Eichorn does in Cutter’s Way is so multifaceted that it really deserves to be analyzed and dissected in acting classes for the next hundred years. The sadness in her eyes is nothing short of agonizing. You want to tell her to pack her bags and leave. You want her to wake up and move on. But she isn’t going to. Cutter is her war. She isn’t just a woman battling for the man she once loved or trying to save her marriage, she is trying to save Cutter’s soul. You want Cutter to see how bad he’s hurting her and apologize. But he’s not going to. Eichhorn is the beating heart of this movie, and it kills me every time I see her last moment on camera where she quietly admits to herself she is giving up.

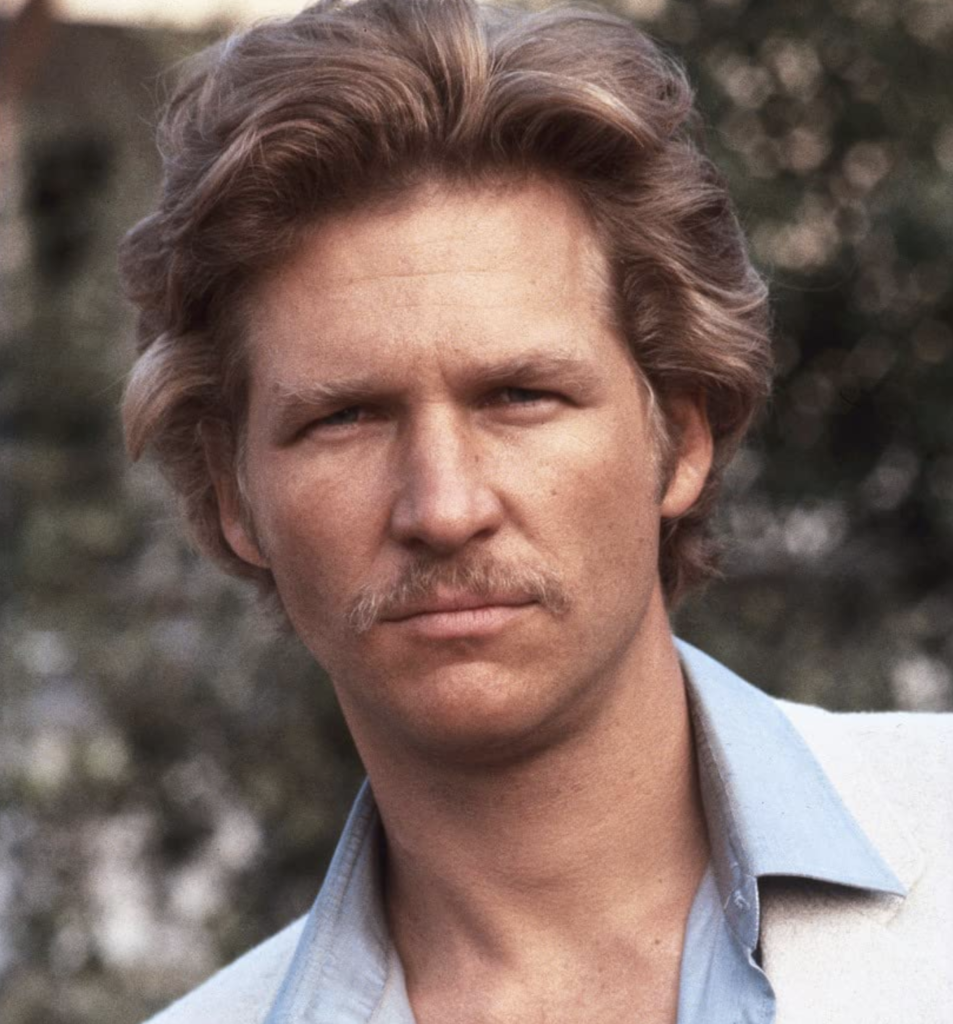

Rounding out the cast is Jeff Bridges as Richard Bone. Let’s be clear, Bridges’ Richard Bone isn’t a good “Dude” in Cutter’s Way. He’s an attractive, womanizing, aimless man, just looking to have a good time. Bone isn’t trying to change the world or find himself. He’s fine with living in the here and now, not interested in the truth or how the world really is. He wants to get laid, have some fun, repeat. Bone’s lack of seriousness and commitment are ultimately one of the real conflicts to the movie. Bone lives in a space between Cutter and Mo. He’s someone who can ignore the truth, doesn’t need hope, and can just say fuck it and float on. That is until the movie drops him in the middle of a murder plot in which he’s a suspect. Throughout the movie he is continuously placed in situations he can’t just ignore. He has to pick a path, and each one a little more serious then the previous one with larger and larger consequences, culminating to the final moment of the film where he has to make a choice that could ultimately change the course of his life. Which brings this back to the heart of what Cutter’s Way is, a movie about people struggling with accepting responsibility of their choices.

None of this happens without Ivan Passer at the helm. Passer, who I was unfamiliar with before viewing this movie, is a master of keeping multiple plates spinning at once. His ability to focus on the immediate nuances of each scene, while crafting an ever escalating conspiracy narrative is incredible. Every character is kept on their journey, while challenged at every point to accept the reality of their life or choose to continue to ignore it. Passer uses Cutter’s evolving conspiracy as a tragic reminder that while characters are focused on the lies the lies they’ve created the truth dies silent.

When a film dances between so many antithetical tones, how does someone tackle scoring it? You call Jack Nitzches, that’s how. Having previously worked on One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, Jack was no stranger to dealing with array emotions and tones crammed into one room. Cutter’s Way is kind of serious, quietly funny, unspokenly sad, questionably mysterious and ultimately ends with desperate characters making desperate decisions. Jack Nitzche’s score so well establishes the films multiple tones in the opening credits with a score perfectly titled, Mo’s Theme. It’s a mix of haunting mystery, absurd conspiracy and a melody that echoes like a memory of something loved, but lost. The score knows exactly when to call on this theme to move between mystery, absurdity and loss.

Shot by a pre Blade Runnner Jordan Cronenweth, he chooses to use natural warm tones focused less on style, but more on capturing a relatable, familiar environment for our characters to live in. Croneneweth’s choice to do this seems like a way to connect the audience to the normalcy of the world these characters live in. They aren’t in some stylist large scale conspiracy movie, They’re in beautiful southern California. The streets are sun drenched, leaving no dark shadows to conceal a mystery. Even indoors, all the scenes are well lit. This is a world that isn’t trying to hide anything. Only one scene deviates from this visual style, Bone’s pivotal first act encounter with the murderer and victim in a rain swept nighttime alley.

Lit with few lone streetlights and a flashing barricade light to cut through the heavy downpour and fog in the air. Cronenweth leans into a choice of heavy contrast, reminiscent of early cinema’s film noirs, calling on that association to help build the tension and mystery for the scene that will ultimately set up the conspiracy plot in motion. Using the environment to obscure the mysterious figure Bone sees is arguably the single most important visual choice in the movie. It’s also not a stretch to assume this lays the groundwork for what Cronenweth will base 2019 Los Angeles on in Blade Runner. After watching this scene it’s not too hard to imagine Deckard and Batty battling on the rooftops above.

Cutter’s Way was initially shelved by United Artists. It was considered unsaleable, due to the fact that they couldn’t find a good way to market the film. It wasn’t a thriller like other conspiracy films of its time or simple love triangle drama. It was more nuanced and deeper than those types of films. It ultimately lands into art houses and finds a life in the new home video market going on to gain some critical success and a strong word of mouth. It’s hard to not think the Coen Brothers caught one of these screenings and were inspired by Cutter’s Way and wrote The Big Lebowski. The similarities between both films are too coincidental. Both star Jeff Bridges as a laid back guy coasting through life, avoiding getting wrapped up in anything too serious until he partners up with his Vietnam Vet buddy to blackmail a wealthy pillar of the community for a crime for which he may or may not be responsible. This isn’t a dig on the Coen’s work, if this movie inspired Lebowski I am forever grateful.

I had mentioned earlier about Mo’s last scene on camera. To me its the most telling moment of the film. It’s takes place in her home after she has made love to Bone (yes she cheats on Alex, and thinks she is finally being seen when she makes love to Bone). As they lay on the couch she asks him to stay the night with her. He agrees to stay and she closes her eyes to drift off to sleep. Bone waits a bit then sneaks out, breaking his promise. Passer chooses to have her face fill the frame the entire time Bone quietly sneaks out. Just before Bone closes the door she slowly opens her eyes revealing she wasn’t sleeping. She was waiting to see if he was gonna hurt or too. As she listens to him leave, she doesn’t cry or get up and try to stop him. We’re forced to see her lay there still and lifeless, almost invisible while filling the entire frame. The very next scene we learn that there has been a fire in her home and she is found dead. If Passer didn’t spend the time on her face I would have been on board with Cutter’s theory that Cord had her killed. But Passer putting the time into letting us see her reaction to Bone leaving tells a different story. During that long tense CU of her face, she acknowledges to her self she is alone, invisible and she is now ready to give up. She may not have died from the fire, but she made the choice to stay in that home while it burned.

I’ve watched this movie two more times since my first viewing and I can’t shake the feeling that I don’t think it’s an accident that the blackmail plot in the movie always seems to take us away from the character’s when they begin to feel vulnerable and start to reveal who they really are. Sure, Cutter’s investigation into Cord and his plot to oust him seems like the movie’s main story, but no one other than Cutter and Bone end up buying this by the end of the film. Alex never has any real evidence proving Cord’s guilt. He connects dots that only he sees and ultimately blames Mo’s death on Cord which finally gets Bone on board (Its easy to assume Bone feels guilty having left her the night before). Cutter’s whole approach just seems like a distraction from how damaged he really is. None of the characters in this film want to face they are broken, or responsible for their own unhappiness they are (Accept maybe Mo in her last scene). I think the only real cover up in this movie is the characters trying to hide from the reality of their own sad lives.

When I put on Cutter’s Way I got way more than I expected. I certainly didn’t envision being inspired to write a piece about it, but that’s what I love about Cutter’s Way and movies like it. Here we are, almost 40 years later and its voice is as relevant as ever. Unfortunately, America is still faced with many of the same issues and disenfranchisement Alex Cutter was seeing and experiencing in 1981. Eichhorn’s role in this film is more pertinent now than it probably was then. She’s a person hiding her depression behind alcohol, sarcasm, and acts of normalcy in hopes that in the morning, life will just have returned to normal. Meanwhile, Bone is doing anything he can to distract himself from acknowledging how bad things are by focusing on living in the moment of immediate happiness. All of this doesn’t sound too different from the current reality in 2020.

*Special Thanks to Bruce Bennett for all his help making my nonsense coherent.